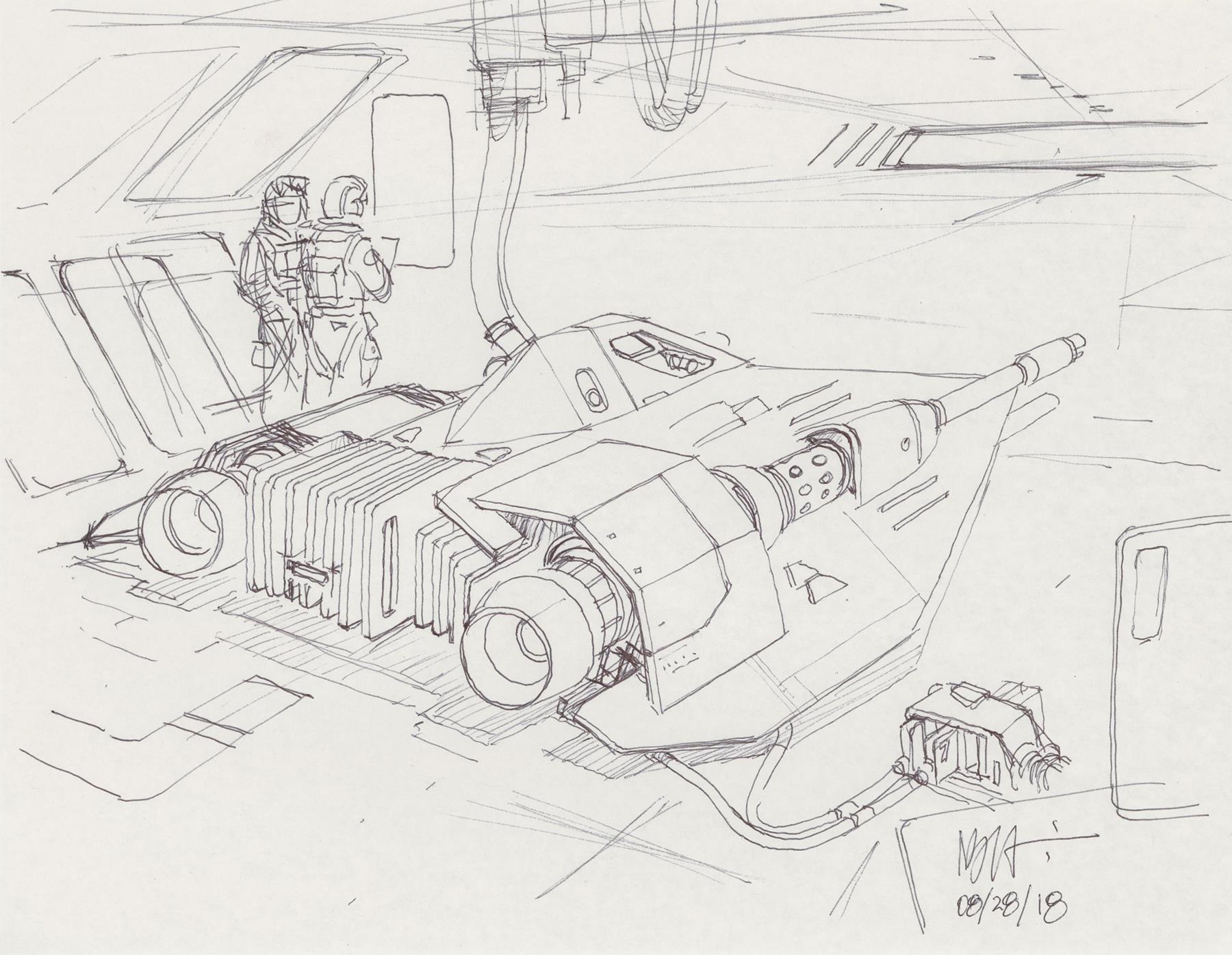

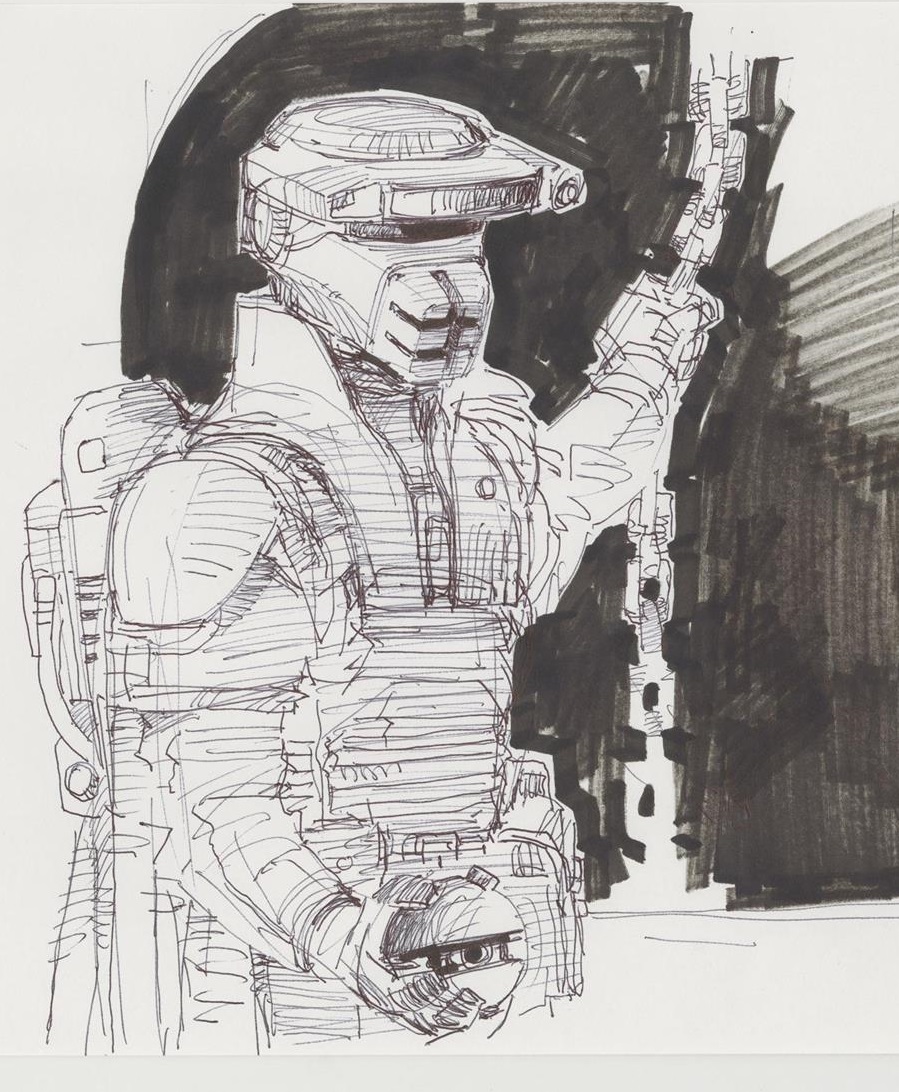

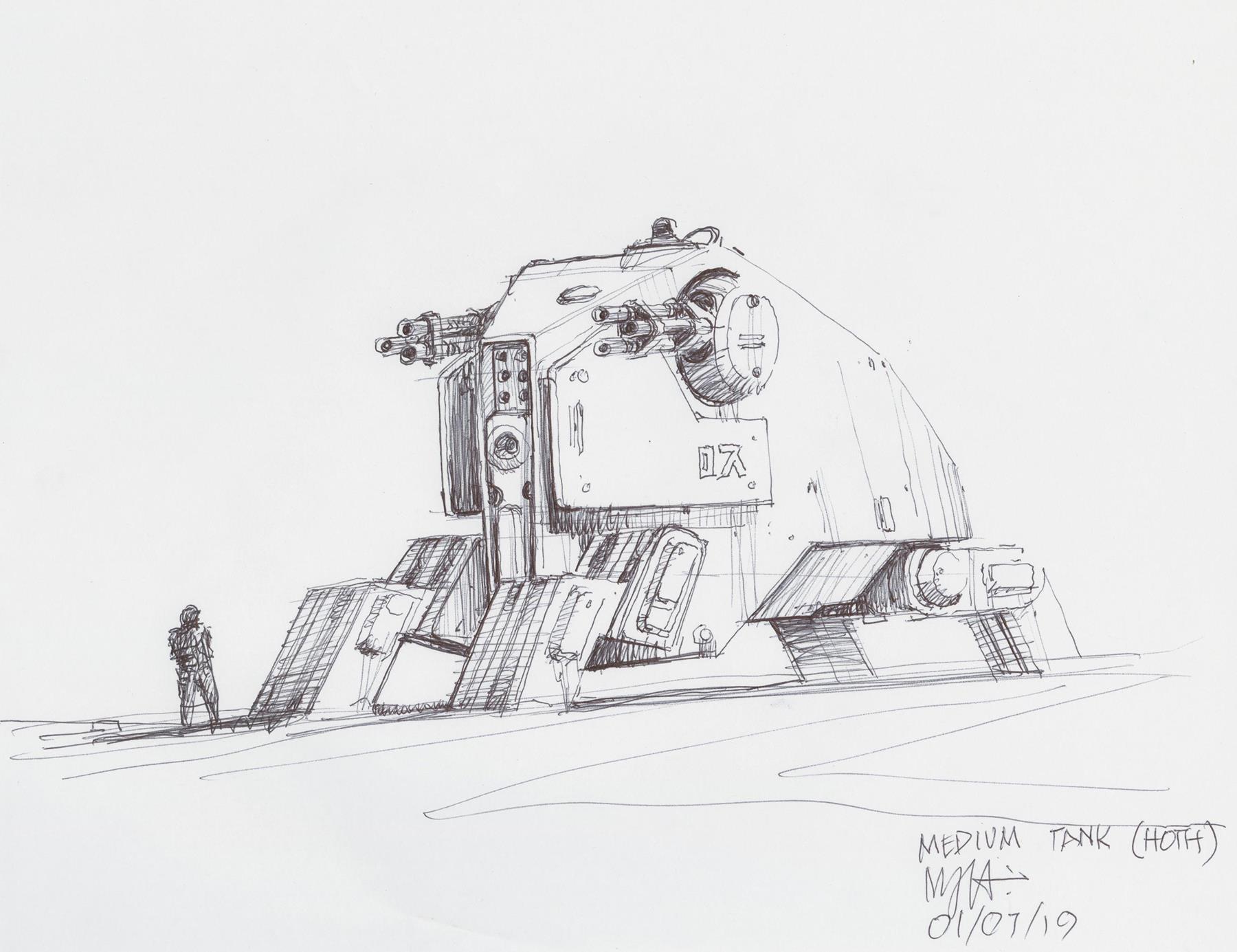

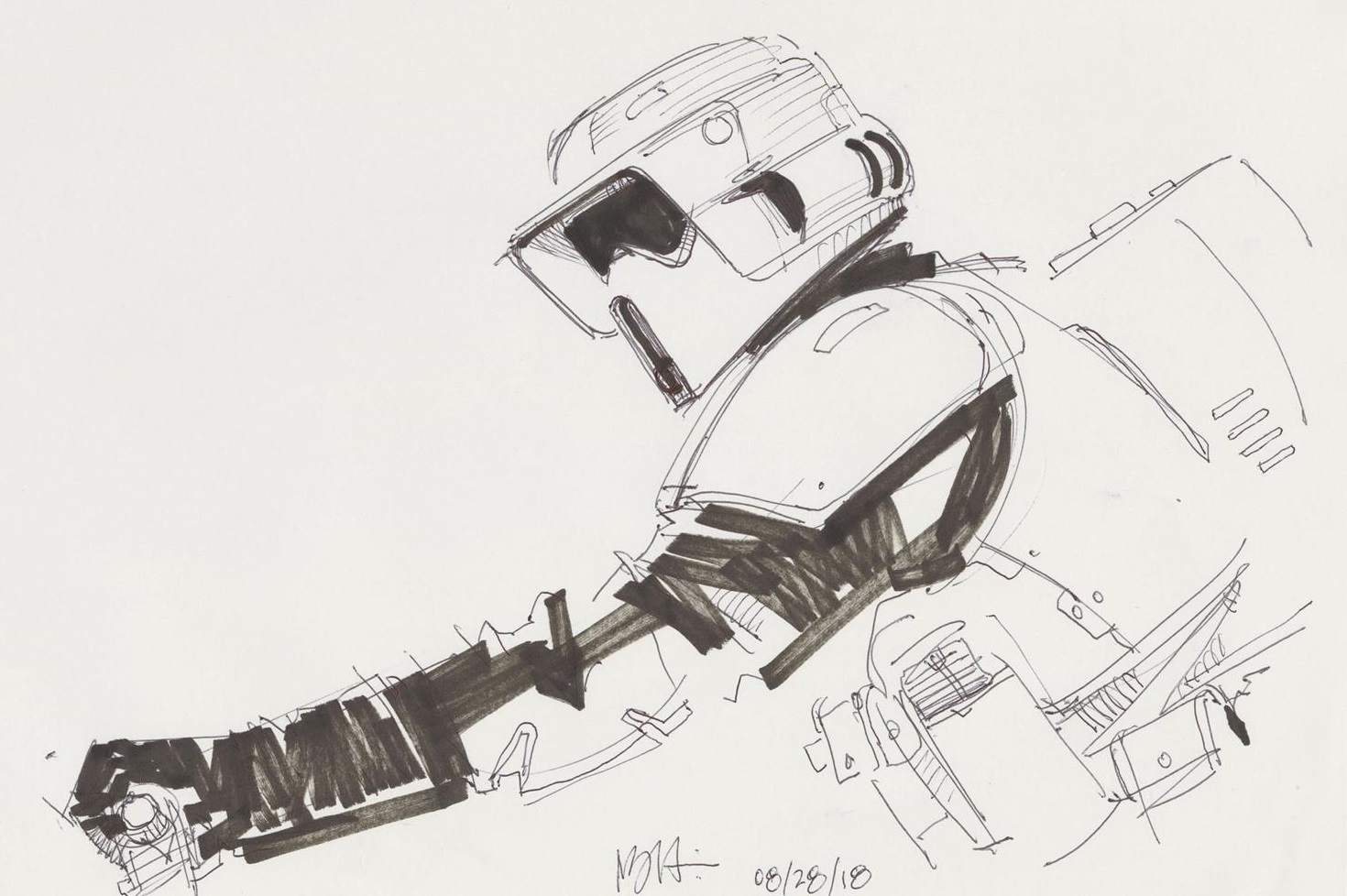

In the Nilo Rodis-Jamero: Reimagined Auction, Propstore presents an exclusive collection of 150 lots of hand-drawn artwork by veteran designer Nilo Rodis-Jamero.

Nilo Rodis-Jamero, an industrial designer by trade, was working on designs for tanks when George Lucas hired him to work with Joe Johnston in ILM’s art department. Rodis-Jamero acted as assistant visual effects art director on The Empire Strikes Back, contributing to many designs including Boba Fett’s famed Slave I ship. For Return of the Jedi, Rodis-Jamero was credited as costume designer but also contributed to all of the early designs on the film alongside seminal Star Wars designers Ralph McQuarrie and Joe Johnston. He is one of a handful of designers who worked hand-in-hand with Lucas on the original films.

Rodis-Jamero worked on numerous other titles with ILM throughout the 1980s, before transitioning to a production designer on films such as Johnny Mnemonic, and later a Producer with John Hughes on films like Flubber. He has been in and around the entertainment industry his whole career, later working on numerous video games as well as stereoscopic film conversions. He has continued to do bits and pieces of design throughout, such as key designs on Buzz Lightyear for the first Toy Story.

In the second installment of this two-part interview, we discuss design in a broader sense. Read on for more…

What would you say George Lucas’s approach to design was when you were working with him?

NRJ: George reacts without thinking. Once every two weeks he would show up and he would sit at the table with just a red marker. You put a sketch in front of him. You don’t explain. You let the sketch explain what it is. Without a word he would either make a mark on it, a red dot on it, or not. So, his reaction was pure reaction. He doesn’t explain because he doesn’t know. Why do you like something when you see it in a movie? You don’t know.

George allows things to breathe. He allows design to migrate from one idea to another. I really like that idea of allowing design evolution, and I really miss that since then.

Did you learn a lot from working with Lucas?

NRJ: George taught me some important lessons and not just about design. Early on during Empire, we had a meeting with some of the key guys at ILM to go over the developing storyboards. It was Joe and I, Dennis Muren, Ken Ralston, Richard Edlund, Phil Tippett, Jon Berg, Lorne Peterson—all those guys. And Bruce Nicholson. We were going over everything with a fine tooth comb. So the first question was raised, what is the color of the Imperial Walker? We never really talked about the colors of the walkers. I think either Joe or myself answered, “white?” And Bruce said, “really white?” And we said, “yeah, white.”

The meeting goes on and finally we’re on page 90 or something, and George stops the meeting. He can see that Bruce is stuck back on the walkers. “Bruce, anything the matter?” And Bruce goes, “Yeah, I don’t know how to pull a matte of white on white on white.” Because everything in the scene had become white. George just said, “Bruce, I’m not asking you to pull a matte of white, on white, on white today, tomorrow, or next month. I may never ask you to. Can you come join us on page 97?”

So fast forward to two years later and the movie is released. Guess who wins the technical Oscar award for that year? Bruce Nicholson, not for pulling a matte of white, on white, on white. Because the truth is that was the least of our problems.

So what I learned from that one meeting is, and I’ve always embraced and followed this since, don’t ever narrow down your focus on one issue. Step back and look at the totality of what the project’s biggest problems are. Solve those problems, and the little ones will solve themselves. Basically, George was saying, “never mind the details. See if you can embrace this idea. And if you can come and follow me, we have a lot to do.”

Do you have to be an artist to be a concept designer?

NRJ: I’m really not an artist, I’m a designer. If you ask me to draw a human face, I cannot draw a human face. I can kind of gesture it. Most of my designs, someone had to interpret them. I became an artist by default, to defend my ideas. And many designers if you notice, they can’t really sketch. They can kind of explain, but they’re not really artistic.

When design is really fluid is when you don’t care and you’re searching for it. Without the search you become an artist. An artist’s rendering of a sketch might be so clear about what it wanted to be that it is devoid of thought, devoid of design surge.

Are there rules to design?

NRJ: What was interesting about Star Wars to me was that Ralph [McQuarrie] was never pushing forward the visual cues. He was pushing them back like it was an old mechanical device. It was never designed to be slick.

And I often hearken back again to who is the original author of this, and I feel beholden to what he had in mind. When I look at Ralph’s design, it was never pushing forward to trendy things like

Now, I understand things have to move on. The acoustic guitar has to move forward to electric guitars. I get that. But when you don’t understand why the original designer set the design direction in that area, and you just go, “I can restyle that, so that it looks like this.” Well, now that’s a styling exercise.

If I’m designing a Porsche, I have an obligation to design it from a Porsche’s point of view. I can’t suddenly go, “well, they’re selling a lot of Toyotas. Let’s do it Toyota-ish.” No. You have an obligation to the history. You have a cannon that is called Porsche.

So when I saw the prequels and there were shapely looking ships I thought, “Where did that come from?” Because that’s a different design direction. The language had changed. The design direction that was originally set was now abolished. And it can be anything it wants to be now because the computer no longer has limitation.

I remember when I saw the original Star Wars, the X-wings looked like they were built yesterday. Not today, yesterday. But yet they flew like they’re tomorrow. It was yesterday’s architecture, yesterday’s limitations, but yet they behave like it’s a vehicle of tomorrow. I thought, “man, I love that.” I like that concept of taking yesterday and moving it tomorrow. I had fun in that world, and everybody involved was really in sync. We all had an obligation to where the design came from.

Follow us on Twitter and Facebook to be the first to know about all current & upcoming Propstore Auctions and more!