The cover piece for our first ever Los Angeles-based Entertainment Memorabilia Live Auction is the 11-foot long filming miniature of the Nostromo from Ridley Scott’s horror classic, Alien. This artifact has been a part of Propstore’s company collection for over a decade, but wasn’t always in the camera-ready shape you see it in now. Read up on this model miniature’s incredible history; from creation, to restoration, to auction.

This is commercial towing vehicle Nostromo out of the Solomons, registration number 1-8-0-niner-2-4-6-0-niner.

ALIEN began as a singular vision of screenwriter Dan O’Bannon. The inspiration, the legend goes, came to him during a bad case of food poisoning. During his gastronomic misery—something that now might now be attributable to the Chrohn’s disease from which he secretly suffered for decades—O’Bannon envisioned an alien creature bursting out from his tortured innards. From that moment forward, the creative spark haunted him like a lucid, waking dream.

O’Bannon had to see it realized – but he didn’t want to tread the path that had been taken before. With the exception of Kubrick’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, science fiction really hadn’t been given a dramatic treatment yet in film. Most of it was like STAR WARS which, while very successful, was the stuff of myth and fantasy to O’Bannon. Not reality.

Instead, he wanted to create a very specific science fiction world. Something that felt lived in. Something inherently real. From the characters to the places they lived and worked to the language they used, O’Bannon saw a fully realized future world that was an extrapolation of our own present. One that drew upon the same apprehensions and issues with which he was faced. To make this happen, O’Bannon and producing partner Ron Schuset began assembling what O’Bannon called his “dream team” of designers and artists: Ron Cobb, Chris Foss, Moebius (Jean Giraud) and the now-legendary H.R. Giger. The dream team set out to breathe reality into O’Bannon’s science fiction world for their new boss, a popular British commercial director named Ridley Scott.

One of the most important pieces of the ALIEN puzzle was the commercial towing vehicle Nostromo, registration number 1-8-0-niner-2-4-6-0-niner. Because, other than a short detour to the planet Acheron (re-dubbed LV-426 by the sequel’s director James Cameron), the whole of the action in ALIEN took place on that fated towing vessel.

The Nostromo, Italian for “mate” or “boatswain,” derives its namesake from the titular anti-hero from Joseph Conrad’s 1904 novel of the same name, a source of great inspiration to O’Bannon. In fact, the fictional mining town where much of Conrad’s novel takes place lends its name to another famed space vessel in the ALIEN universe. That town’s name? Sulaco.

The Nostromo spacecraft was conceived in the vivid minds of Ron Cobb and Chris Foss, both of them already famed conceptual artists when they began work on the film. Cobb came from an industrial background, referring to himself as a “frustrated engineer,” whereas Foss was more “Giger-esque” in his approach to design, dreaming up a spacecraft that felt more other-worldly, or even alien in their aesthetic. The two sequestered themselves away for months to work on creating the Nostromo from scratch. Cobb was meant to tackle the interiors—seen as a much more engineering-like task—while Foss was intended to divine the ship’s exterior. However, the two found that their individual creative processes were not mating up. Cobb’s designs began with function and found their way to form whereas Foss’s approach was the opposite. That’s probably why, after months of work and dozens of conceptual sketches, it was Ron Cobb’s extremely engineer-like design that landed on the desk of visual effects supervisor Brian Johnson.

The challenge now? Someone had to build it.

Someones, that is. Brian Johnson assembled a talented design team composed of now-famous effects artists such as Nick Allder, Ron Hone, Simon Deering Jon Sorenson, Martin Bower and Martin Gant. Their work would be done at Bray Studios outside London. The Nostromo began life as a six-inch conceptual model built by Terry Reid. The team used this three-dimensional sample to develop the design with director Ridley Scott. “There’s nothing like handing a director a model for him to play with and twist around,” Johnson recalls. He also remembers making frequent trips from his visual effects headquarters at Bray to the director and production staff at Shepperton as the Nostromo slowly evolved.

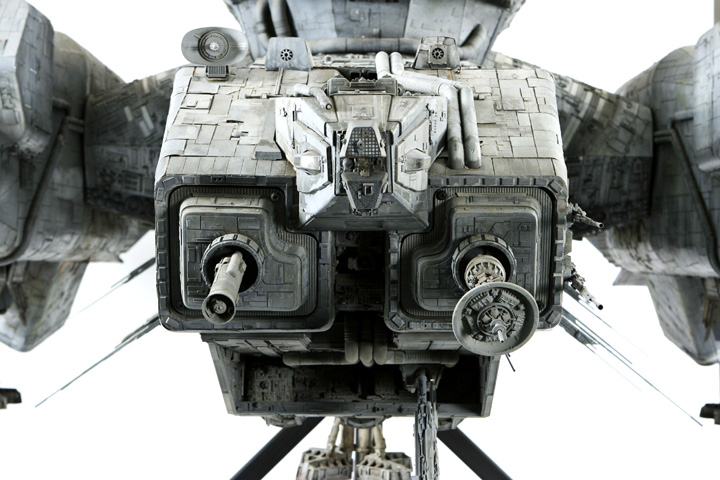

Once they had Ridley’s blessing (no easy feat, if you ask them), the bevy of designers at Bray began building the eleven by seven foot model, ironically called a “miniature.”

The Nostromo started as no more than a steel frame that was constructed to provide skeletal support to the massive (estimated at 500 pounds or more) final build. Chunks of solid wood were shaped and mounted on the steel to serve as the vessel’s “musculature.” Once the Nostromo had a sound understructure, Brian Johnson’s team went to work applying the “skin” to the Nostromo’s industrial surface. This group of artisans called themselves “The Widgeteers,” a dedicated team of detail-oriented engineers, applying hundreds of little plastic widgets in a tedious labor of madness and passion.

The Nostromo’s outer surface was brought to life via a method known as “kit-bashing” where the modellers would raid hobby shops for off-the-shelf model kits and then use the parts from those models to create the very functional-looking outer surface of the miniature. In the case of the Nostromo, certain model kits were “bashed” again and again to give the Nostromo life. Parts that were required in high multiples were sometimes obtained in batches from the models’ manufacturers. The most popular models farmed for their parts? A British Matilda tank from World War II, NASA’s space shuttle, and Darth Vader’s TIE-Fighter. The effects team then used chloroform to literally melt the plastic parts so that they could be shaped to the curving surface of the miniature. Once they were shaped, the chloroform would eat away at the thin styrene model parts, thus bonding them to the wooden understructure. With that much surface area and that many parts, one sincerely hopes that the modelers employed OSHA-approved ventilation during the build.

The build process would not be a streamlined one. Ridley Scott, like any mad genius (see Messers: Hitchcock, Kubrick, Cameron), was not a director to remain “hands off” during pre-production. He was constantly tinkering with not just the Nostromo, but all aspects of the film’s design. As tends to be the case in filmmaking, this didn’t sit well with his artisans. In recalling their work at Bray in 1978, they remember the frustration of having to change the physical model so many times even after it had been assembled and painted. In fact, the Nostromo was intended to be yellow to make it truly appear like an industrial space tugboat. This plan lived long enough that production photos exist of a very real and very yellow Nostromo. But, as the reader might agree, the look of this proved odd, somehow minimizing its imposing presence and muting the enormous amount of detail on the ship’s surface. At Ridley’s direction, the Nostromo was repainted a weathered gray, complete with all the grime and dirt that would be collected over decades of space travel.

As the design team likely suspected, the Nostromo’s evolution was not over. During production, Steven Spielberg’s CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND was released to much fanfare. Upon seeing the breathtaking shot of the alien ship landing on Earth, Ridley was said to have declared, “We need more lights!”

There was already a bird’s nest worth of (glass) fiber-optics that electronics whiz John Stevens snaked through the Nostromo to create dozens of tiny lights that could be lit from a single source. But even with all that work, there was still nowhere near the amount of lights seen in CLOSE ENCOUNTERS. Rather than setting back production by gutting the Nostromo and re-lighting it, a supplemental “belly” was built for the ship. This one with a massive amount of lights that could be attached to the existing model. The belly was cobbled together with wheat grain bulbs and whatever else the visual effects team could find lying around Bray Studios. It wasn’t a refined process, but if the film itself is suitable evidence, the effect ended up working seamlessly. This bit of movie magic can be seen in all its brilliant, hazy glory when the Nostromo comes in for a landing on the rocky, desolate planet where Kane picked up his little friend.

Also built to augment this surface sequence was a large-scale landing leg. Though still a miniature compared to the full-scale, twenty-five-foot tall leg built at Shepperton studios, this insert leg was big, over seven feet tall, making it comparable itself in size to the entire Nostromo miniature. This filming insert was given the task of providing a more dramatic entrance for the Nostromo by crushing a rock during the ship’s landing on the alien planet. Ridley was obsessed with the scale of the Nostromo, always wanting it to appear vast and cavernous. So much so that even with a full-scale, twenty-five-foot tall landing leg built, Ridley dressed small children (one of them his own) in space-suits to make the leg—and therefore the ship—seem twice as large as it physically was.

Despite the challenges of production, the reminiscing effects team looks back fondly on the experience and are all clearly quite proud of what came of it. The Nostromo has left an indelible mark on model-making and science-fiction art direction. The model itself now survives as both a monument to filmmaking history and an objet d’art that instantly evokes the noir-ish, industrialized future that Dan O’Bannon had envisioned. But when studying the history of sci-fi filmmaking with the very artisans who shaped its history and talking about the glory days of physical builds and motion-control cameras, it’s only a matter of time before the dreaded initials “C.G.” make their way into the conversation.

Some are practical about it, saying that there are great cost-savings that come into play with computer-generated models and that the “virtual” ships can be made to move in a way that’s still not possible even for top of the line motion-control rigs and modern filmmaking techniques.

But there’s a flip side of this coin that perhaps tarnishes the benefit.

“Computer generated aircraft don’t fly properly,” one of the original ALIEN visual effects team members said. It appears that, for all the algorithms, study, and technology, computers still have not figured out the physics of the real world. There is a great nostalgia present for the “good old days,” and maybe even a sadness that a stunning filming miniature like the Nostromo may never be built again. But others were more blunt in their assessment of the modern techniques – “I hate this computer-generated crap.”

Wherever the science fiction film genre may have ended up after the last thirty years, it got there in large part due to the May 25, 1979 release of ALIEN. The film, though initially experiencing a “mixed” reception from critics, was a major commercial success. It raked in over 80 million dollars in the United States alone, nearly ten times its production budget. Audiences were thrilled and horrified, and many couldn’t stop going back to the theater to experience it all again. Religious zealots so reviled ALIEN’s “demonic” imagery that they set fire to the space jockey model when it was put on display at Grauman’s Egyptian theater in Los Angeles to promote the film.

Ridley Scott’s coming out party was a reckoning.

ALIEN took two genres that critics looked down their noses at—sci-fi and horror—and turned it into intellectually provocative, adult, elevated fare. The film won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, thanks in large part to the work of Brian Johnson’s team and the visionary design of H.R. Giger. Many films that came after would mimic ALIEN (and benefit from riding its coattails), but few since, even thirty years later, can be rightfully held up beside it.

But, all was not guaranteed. Brian Johnson recalls approaching the commercial director’s hire onto ALIEN with trepidation. “When I first started on Alien, Walter Hill was going to direct. I had no idea that instead of an accomplished screenplay writer who had also directed HARD TIMES and THE DRIVER… a [British] TV commercials director of repute and director of THE DUELLISTS… would take ALIEN to the heights that few directors would have equaled.” Johnson maintains a warm place in his heart for Ridley Scott, who he compares favorably to the visionary Stanley Kubrick for his shot composition. “Ridley had a massive influence on every effects shot and in my view [is] an equal to Stanley Kubrick in terms of composition of each image. Unlike Kubrick, who claimed the effects Oscar® for 2001 [A SPACE ODYSSEY]… Ridley did not claim to have title to the Alien effects Oscar. For that I am personally very grateful!”

And so the ALIEN production was then broken down, the sets were struck and the writer, director, producers, and crew carried on with their careers. But what about the Nostromo? What does one do with a spaceship that takes up seventy-seven square feet of space and that takes a team of men just to move it from room to room?

Any suggestions from you or Mother?

No, we’re still collating.

The “basement” of Los Angeles resident Bob Burns has become a famous Mecca to sci-fi and horror fans everywhere. In truth, it’s really more a first floor edition as few Los Angeles residents have honest-to-goodness, dug-into-the-earth basements. But Bob’s private collection is an altar to all that is holy in genre filmmaking. His connection to sci-fi and horror stretches back to the campy heyday of the 1950s and 1960s when he worked as a producer of film and television and also as the host of a popular children’s TV program. During this time, he met and mentored many young geeky hopefuls who would eventually become visual effects wizards themselves. Burns was a collector for most of his life, so when his former protégés began making the models, props, and costumes that would be immortalized on film, his private museum saw a marked increase in donations.

The Burns collection was further bolstered by the popular Halloween show that he ran every October. Just as Burns isn’t your typical collector, he did not put on a typical Halloween show. He put on full-scale haunted houses that would see neighbors, travelers, and even industry folks lining up for blocks just to be a part of the realistic experiences Burns and his effects crew would conjure. After ALIEN was released in 1979, Burns didn’t even have to think about the theme of that year’s show. It was going to be ALIEN. What began as an innocent call to 20th Century Fox simply looking for permission to put on the show created, well, a monster. In fact, the response Burns received still floors him. Fox not only gave Burns permission. They gave him props.

With authentic creatures, set pieces, costumes, and props from the hit movie, the Halloween show was a runaway hit. So pleased was 20th Century Fox with Burns’s sci-fi-horror spectacular that they ended up donating many of the ALIEN props, models, and costumes that had been shipped in from England’s Shepperton Studios to Burns’s private museum.

It was here that the Nostromo would make its next stop. Burns knew that if he did not agree to take the massive filming miniature into his museum—where it could be visited and enjoyed for years to come—it would likely be abandoned or destroyed. Burns, ever the film historian, simply would not have that. The problem was, even if his generously-proportioned basement existed yet (it didn’t), it wouldn’t be big enough to house the space-hogging space tug. And so, the Nostromo was delivered to Burns where it was lowered into his driveway… by crane.

Visitors came and went and saw and enjoyed the Notsromo where it rested, right there in Burns’s driveway. But there was really no other place for it to go. So that’s where the Nostromo would live on for nearly two decades, cared for the best way Burns could manage with the resources he had available—protected from the elements with a series of waterproof tarps.

Unfortunately, even with the best shelter Bob could provide, time still would not be kind to the Nostromo. Between drenching Southern Californian rainy seasons and wood-and-plastic-splitting heat of the summers that would follow, the miniature was tortured by nature for some twenty years. Although some have questioned the propriety of the Nostromo’s living quarters during its time in Burns’s collection, it is very clear to one who reviews the history that, had it not been for the generous donation of his driveway, the Nostromo would not have survived at all. It was not the ideal storage facility, but Burns’ driveway was a better place for the Nostromo than an industrial dumpster at 20th Century Fox.

In the late 1990s, Burns knew that the Nostromo was in rough shape. He sent up the bat-signal (no, that particular prop is not in his basement) and called in a favor from one of his many close relationships in the visual effects industry: Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger of KNB Effects. Not wishing to see such a beloved piece of movie history endure any more torture at the hands of the San Fernando Valley, Nicotero and Berger happily took the Nostromo in like some kind of sci-fi foster child. KNB had full intent to rehabilitate and restore the ravaged miniature themselves, but real movies and production gigs kept preventing them from completing their passion project. So there the Nostromo sat for nearly eight years, hurting but now dry and cool, tucked away in a storage locker.

The hope for a rescue of the marooned spacecraft via a complete restoration thrived as a persistent tease, but it was not a reality.

At least not yet.

When last we left the Nostromo, it was an ailing derelict, lost to the punishment of time and the elements. All hope seemed lost… But then, a beacon appeared on the horizon.

Enter: Stephen Lane and his rescue ship Propstore.

In 1998, the England native Lane turned his hobby—collecting original movie props and costumes—into a full-time business. But his vision was not that of a stock retail operation—buying props, marking them up, and selling them to collectors. Instead, Lane saw himself and his cohorts as “movie archaeologists,” scouring the world for the hidden treasure troves of props and costumes that were just waiting to be found. Sure it was his business. But Stephen was a collector first and foremost. His work drew from a well of immense passion and was pursued with a largely conservationist bent. Countless important film artifacts have been lost to time and to the rubbish bin over the decades and Lane and his growing army of collectors sought to put an end to these travesties, one prop at a time. Propstore grew into a behemoth over the next decade-plus, amassing over 15,000 square feet of warehouse and office space in two major cities on two different continents: London and Los Angeles.

This made the Nostromo an ideal candidate to be awoken from its hypersleep in KNB’s storage facility.

In 2007, Lane and head of Los Angeles operations Brandon Alinger worked out a deal with KNB that would see the Nostromo finally resurrected and put on display where film fans could enjoy it again. The model was freighted into Propstore’s Los Angeles office where the Nostromo’s condition was fully assessed. The seams—both of the styrene detail work and the wooden understructure—were pulling apart. The wood had splintered, cracked, eroded, and shrunk. Years of rain had soaked into the wood and dried it out, the same conditions that can lead to dry rot. The Nostromo was not in good shape. The miniature was in desperate need of restoration, but the work was beyond Propstore’s internal resources. Bring back life form. Priority One. All other priorities rescinded.

Okay, fine. But who the hell do you call when you need to restore a circa 2087 Commercial Space Tug? The ideal scenario for the restoration would have been to reunite the model with its parents, Brian Johnson and his ALIEN visual effects team. Unfortunately, the Nostromo’s bulk and general condition precluded the possibility of it being sent back to the United Kingdom.

So Propstore met with a number of effects houses in Los Angeles before deciding on the legendary Grant McCune Design, the guys who practically invented sci-fi movie model making.

Pulling into their parking lot deep in the baking heat of Los Angeles county’s San Fernando Valley, the Grant McCune Design facility doesn’t look like much. Except the parking lot itself is a landmark in movie history. In 1977, Grant McCune Design’s—then the very first incarnation of Industrial Light and Magic (ILM)—parking lot was the site of the filming of the famous Death Star trench from George Lucas’s original STAR WARS. The eighty foot long trench was too expansive to house inside ILM’s facility, so they built it outside. In the parking lot.

Grant McCune and his team, including Don Trumble, Bill Short, and visual effects legend John Dykstra himself, designed and built the models that made STAR WARS well… STAR WARS. But when the team was approached with the opportunity to create the practical visual effects for STAR WARS, they had never even built a model before! They were already accomplished tinkerers and innovative builders, so the prospect wasn’t terrifying: it was a challenge.

It was through the resulting process that many techniques that are now common practice in model-making were invented, including using fiber optics to create internal lighting and George Lucas’s “used universe” concept, which meant making the model look old and lived-in, despite the fact that it had been built in just a few weeks. A crucial part of this visual effect was “kit-bashing,” and the original STAR WARS saga remains the finest example of kit-bashing in practice. After George Lucas purchased ILM and moved it to Northern California, John Dykstra and Grant McCune opened their own effects shop. Apogee would go on to explode in the 1980s heyday of practical visual effects (before the shift to computer generated effects). Before it restructured again in the early 1990s and became Grant McCune Design, Apogee was the biggest model-maker working in the movie business.

With Grant McCune Design’s unmatched pedigree, Propstore saw his shop as the perfect rehabilitation facility for the ailing Nostromo.

Thankfully, Grant McCune Design modeler maestros Monty Shook and Jack Edjourian agreed to tackle the restoration. Both designers had worked on a number of popular films, but the chance to restore an icon like the Nostromo thrilled them. When they first saw the Nostromo in Propstore’s storage facility, Shook and Edjourian were amazed at its sheer size. But they were also amazed at the overwhelming amount of work that lay in front of them.

In fact, an initial inspection of the wooden musculature had them concerned that the degradation was too far gone for a true restoration versus a scratch rebuild. They worried about dry rot and even termites having afflicted the wood, but fortunately, a more detailed inspection revealed that the model’s robust initial construction and a little bit of luck had preserved the Nostromo from a terminal diagnosis. Even now, Edjourian and Shook still marvel at the Nostromo’s steel support frame, as they had never seen anything that heavy-duty. Still, Grant McCune Design was amazed that the model lasted as long as it did. The wood had worn so thin that it was a wonder that it was still in tact. To bridge the different sections of the ship, the original design team used a thin ply that might have been weather-sealed, but no evidence of this remained. It seemed like the Nostromo had just barely held on, knowing this succor would come.

It was very important to both Propstore and to Grant McCune Design to keep the Nostromo as true as possible to its original makeup. This meant fixing broken and worn parts rather than replacing them, even when the fix was more time-consuming than a casting or a replacement. This was going to be an archival-quality restoration, and one handled with the utmost of expertise and care.

Agreements were made and Grant McCune Design set to work.

The first step was a thorough cleaning of the model’s hollow interior, an unenviable task that fell on Edjourian’s shoulders. And he couldn’t believe what he found. He was pulling out seemingly endless fistfuls of rotting leaves and other awful-smelling organic filth. How did all this crap find its way inside the narrow nooks and crannies of a model spaceship? Well, much like the movie ALIEN’s Nostromo—and much to Edjourian’s horror—Propstore’s Nostromo also had a stowaway.

Something has attached itself to him. We have to get him to the infirmary right away.

What kind of thing? I need a clear definition.

An organism. Open the hatch.

Thankfully, this Nostromo’s dark passenger was not an acid-bleeding xenomorph whose structural perfection was only matched by its hostility. Nor was it Captain Dallas’ mother-in-law.It was an opossum. A very dead one who had left behind only her skeletal remains as evidence of her one-way visit to the Nostromo. Not wishing to find other such surprises or tear out the nest of (no longer functional) fiber optics that also lurked within, Edjourian began photographing the interior of the model as he dug deeper inside. To his surprise, the opossum didn’t die alone. Inside, he found a second, complete opossum skeleton, possibly that of a mate or an adult offspring. But to sci-fi and horror guys, this revelation wasn’t horrifying. It was kitschy. In fact, at the time of this writing, the opossums were being lovingly reassembled at Grant McCune Design as a piece of macabre model-making memorabilia.

In addition to California wildlife, Edjourian also found an entire CO2 gas system inside the Nostromo. This was used during the landing sequence to create the dramatic exhaust vapors that Ridley Scott so loved to employ in order to create a “film noir” atmosphere in his sci-fi films.

Once it had been thoroughly cleaned out, a proper restoration could begin. They reclamped and reglued the suffering wood understructure in an effort to get the model both symmetrically and structurally sound again. As they snapped a photographic record of the Nostromo’s original state for reference, they peeled off the plastic parts to get to the softened wood beneath. This process is what led them to the surprising discovery that chloroform was used as the original bonding agent, something that certainly would not be done today. The repairs also yielded physical evidence of the Nostromo’s aborted yellow paint scheme, as there were still traces of the nautical yellow in the cracks and crevices of the now flat-gray ship.

The shoring up of the Nostromo’s structural integrity alone took weeks worth of man-hours, but was the most important part of the restoration as it was the work that would hopefully ensure the Nostromo decades of longevity to come. Once the model was structurally sound again, it was time for the detail work.

That’s where the real fun began for the self-professed “model geeks” at Grant McCune Design. “It was the world’s greatest jigsaw puzzle,” Jack Edjourian recalls. The restoration team was looking at tables and table’s worth of tiny styrene pieces, most of them just a few square inches in size. But they had a virtual reference library of photographs of the original Nostromo thanks to Propstore’s unparalleled research efforts. Also, a fortunate happenstance of the way the Nostromo was weathered by the elements was that the years of dirt and rain left little outlines on the wooden understructure where it had run into the seams between the styrene detail pieces. Mother nature had left behind a template for what the original model looked like! So all Grant McCune Design had to do was figure out what went where. Still no small task, but with the pieces that they rescued and with a supplemental bag of parts that Bob Burns had preserved indoors, the Nostromo was actually starting to look like herself again. Once these pieces had been cataloged and fitted, it was clear what was missing and where it was missing from.

Recall that the Nostromo was originally constructed using the parts from a few off-the-shelf model kits. Back to our old friend “kit-bashing.” Well the reason we know this is not necessarily due to a thirty-year old memory of a British visual effects team member, but because of Grant McCune Design’s own Jack Edjourian. Using his encyclopedic modeler’s mind, he went about identifying the parts used by the original “widgeteers.” In his investigation, Edjourian was surprised to discover that virtually no gang-molding had been done by Brian Johnson’s effects team. That means that instead of picking a part that they liked and casting it in silicon to make as many copies as they needed, the design team used original parts from the model kits they liked. Again and again and again. This tedious, iterative process amazed everyone at Grant McCune Design. But Johnson sheds light on the mystery, “One reason we didn’t do any gang molding was because in the UK at that time the products were somewhat unstable… I saw results that had not lasted many weeks in front of hot lamps and we had to shoot at high speed because of the dust effects…”

The Nostromo was a “labor of love” back in 1978, too.

So a-kit-bashing Edjourian and his team went. He identified the parts he needed and the models from which they originated and went to his model supplier and started buying up the old kits again. In the model kit business, not much changes over time. If the model is still being produced, the original dies are used over and over so the parts Edjourian would be finding (if available) would be identical to the ones used three decades earlier. There was a bit of trepidation at the end of this process as Edjourian was looking for a particular British Matilda tank model that was still around but a bit rare. As fate has it, Grant McCune Design’s model supplier happened to have just one of these left in stock.

Fortune suddenly seemed to be following the Nostromo’s restoration just as misfortune had shadowed her for her prior twenty-seven years.

Though the original effects team hadn’t employed gang-molding, Grant McCune Design wasn’t about to hunt down of model kits just for the sake of one-upsmanship. Whenever possible, original parts from the Nostromo were used for the mold master. Then, the parts needed in multiples were thrown into two-part silicon molds and Grant McCune Design could make exact duplicates of all the parts they needed in durable urethane plastic. Over thirty molds were created in order to fabricate parts that were completely accurate to the original. All viable parts could then be heated and shaped onto their place on the model’s surface.

One piece at a time, Grant McCune Design trudged forward. Molding, pulling, heating, shaping, gluing.

During this time-consuming process, freelance modelers would come into Grant McCune Design to do visual effects work on a film, see the Nostromo being restored, and cleverly worm their way into the restoration process. To a visual effects artist, the Nostromo is like an original Shelby Cobra to a motor-head: if you see one being restored, you want to get yourself under that hood. Thus, in a shop full of model geeks, the Nostromo never found itself in want for labor.

Until his passing in late 2010, Grant McCune himself participated in a solely supervisory role at his shop, and still spent a good amount of time at the facility during the restoration in 2007. Upon seeing his team restoring the Nostromo, he was said to have remarked: “We didn’t win an Academy Award because of that.” At the 1979 Academy Awards, Apogee lost their Oscar® bid for their work on STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE to Brian Johnson’s ALIEN visual effects team. But Shook had a salve for McCune’s old wound, “Well the good part is, we’re getting to fix it.”

The structure was sound and the kits were bashed. It was time to paint the Nostromo. But Grant McCune Design couldn’t have an old, beat-up space tug roll out of their shop looking like it had just come out of Weyland-Yutani’s factory. They had to weather it. After studying their extensive photographic reference and evidence they could collect from the cleaner pieces that had been spared from outdoor storage, Shook and Edjourian had a pretty good picture of what the Nostromo looked like when it was wheeled onto the soundstage at Bray Studios back in 1978. The intent was not to alter the original paint wherever possible, instead focusing only on the restored sections of the ship while using the sections with the original paint as a guide. The real trick was to create a seamless effect for the Nostromo that made it appear as though it had been painted and weathered in one application with a single set of materials, even though the model had really been painted by two different effects teams, thirty years apart from one another.

To achieve this look, Grant McCune Design painted the ship in sections, hitting one at a time. They applied six different tones of gray in a patchwork, favoring the paintbrush over the airbrush for a less “deliberate” look. Then, to make the ship appear weathered, they went over the refurbished sections with a chalky wash before finishing it with a wet, dark wash that was meant to “age” the new paint. This was all done while ensuring that the value and texture of the restored sections matched the adjacent sections with the original paint job.

The entire restoration took the better part of a year in between deadline-driven film and TV jobs, with Shook, Edjourian and four other artisans spending the equivalent of three months of 40 to 50 hour workweeks on the Nostromo. About twenty percent of the restoration—over 400 man-hours—was spent on the structural repairs alone. But the bulk of the work, some sixty percent of it, Shook guesses, was spent “widgeteering,”—figuring out what parts went where, what was missing, what model kits the pieces could be farmed from, gang-molding and then shaping and application. The remaining labor was the paint job and final assembly.

This time, there would be no self-destruct sequence for Ripley’s Nostromo. After being on the very precipice of a one-way trip to a sci-fi junkyard somewhere outside Los Angeles, she was alive and kicking one again. The final product is visually stunning on its own. Compare it to photos of the model’s condition prior to the restoration and its current state is a minor miracle. The Nostromo’s new owner Stephen Lane was equally taken with it.

“I’m so proud to have now become part of the history of this incredible model. She is a sight to behold and I encourage anybody who is visiting Los Angeles to come and see this phenomenal piece of work in person.”

In the end, the Nostromo’s restoration goes far beyond being some hobbyist’s passion project. It’s the work of a film historian attempting to preserve a crucial artifact from one of the medium’s genre landmarks. Without Bob Burns’s initial move to save the Nostromo from the rubbish pile at Bray Studios, KNB Effects’ rescue and, most importantly, without Propstore’s final intervention, the fans and the annals of movie history would have only memories to cherish. Instead, thanks to the dedicated and forward-looking few, we have the Nostromo. In her full, former, industrial glory.

Final report of the commercial starship Nostromo, third officer reporting…

The other members of the crew, Kane, Lambert, Parker, Brett, Ash and Captain Dallas, are dead. Cargo and ship destroyed. I should reach the frontier in about six weeks. With a little luck, the network will pick me up.

This is Ripley, last survivor of the Nostromo, signing off.

Thanks to guys like Bob Burns, Greg Nicotero, Howard Berger and Stephen Lane, this Nostromo dodged the climatic self-destruct sequence. And now, it can be enjoyed by ALIEN and sci-fi fans old and new for generations to come.

This article is dedicated to the memory of the late, great Grant McCune, who kit-bashed many of our childhoods, making us the geeks we are today.

Thank you, Grant. You will be sorely missed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

ALIEN Visual Effects Team:

Nick Allder, Martin Bower, Simon Deering, Brian Eke, Martin Gant, John Hatt, Ron Hone, Guy Hudson, Brian Johnson, Andrew Kelly, Phil Knowles, Dennis Lowe, Roger Nichols, John Pakennham, Bill Pearson, Phil Rae, Jon Sorenson, and Neil Swan.

Grant McCune Design Nostromo Restoration Team:

Monty Shook, Jack Edjourian, Scott Burton, John Eaves, Olivia Miseroy, Jason Kaufman, Eric Tucker, and David Venegas.

Also, special thanks to:

Bob Burns and Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger of KNB EFX Group.