From electrifying chase scenes to hair-raising booby traps and a lot of snakes, the Indiana Jones franchise has given us an endless amount of visual thrills, tension-breaking humour and whip-cracking escapism.

On June 30th 2023, a dark fedora, a coiled whip and a dusty, well-worn leather jacket will be donned once more by one of cinema’s most beloved characters in the fifth – and most likely final – film in the Indiana Jones franchise, The Dials of Destiny (2023).

“I miss the desert. I miss the sea. And I miss waking up every morning wondering what wonderful adventure the new day will bring to us.”

Sallah (John Rhys-Davies), Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023)

The upcoming Indy film Dials of Destiny is set to deliver the hallmarks of a classic Indiana Jones adventure; globe-trotting escapades, skin-of-your-nose escapes, the return of the Nazis and an enigmatic artifact driving the story forward. Although the plot has been kept under tight wraps, what we do know is that the story takes place in 1969 amid the cultural backdrop of the NASA space program, the rise of nuclear power and new technologies, and the turbulence of the cold war where a black and white division between the good guys and the bad guys no longer exists.

It also marks the first film in the series not to be directed by Steven Spielberg. Instead, the mantle has been passed to James Mangold, director of Logan and 3:10 to Yuma. Aiming to keep the film’s essence as authentic to the franchise as possible, Mangold reveals the film will mostly rely on practical effects and has rejected the use of The Volume (a VFX technology developed by Lucasfilm’s Industrial Light & Magic, which creates photo-realistic backgrounds on a 360-degree LED screen and eliminates the need for outdoor physical sets). This decision may have been influenced by the underwhelming reception of Indiana Jones’ fourth caper, The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), which was widely criticized for its heavy overuse of CGI.

George Lucas’s VFX company Industrial Light Magic has worked on all four of the Indiana Jones film and are – unsurprisingly – returning to provide their movie magic for the fifth. Throughout the franchise, the masterminds behind ILM have created and developed astounding practical and visual effects which have bought all the action, thrill and gore to life.

So whilst we wait with baited breath to see the next installment of the Indiana Jones franchise, let’s take a look back at some of our favorite of ILMs progressive and imaginative use of visual effects throughout the original trilogy before the use of CGI even existed…

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) | The Ark Of The Covenant

Widely considered the most beloved film of the series, Raiders of the Lost Ark won four Oscars for visual effects, sound mixing, film editing, and production design which clearly demonstrates the film’s technical ingenuity. One scene that relied heavily on ILM’s creativity was during the film’s final sequence when the Ark is finally opened and unleashes all hell.

After the Ark is opened, billowing smoke rolls out, and ghostly spirits emerge and float eerily around the watching Nazis. The features of the apparitions, which at first appear angelic, quickly turn into grotesque skeletal beings. Finally, the energy of the Ark erupts into flames, bolts of which shoot out, killing the terror-stricken army and the heads of Belloq and his cohorts shrink, explode and melt before being engulfed by the whirlwind of flames.

To create this haunting sequence, large flashbulbs used for high-speed photography were attached to the extras via rigs that went inside their shirts and over their shoulders. These were plugged in by a wire that ran down their leg and triggered by a button that fed down their arm. The actual flaming bolts were then later animated by ILM.

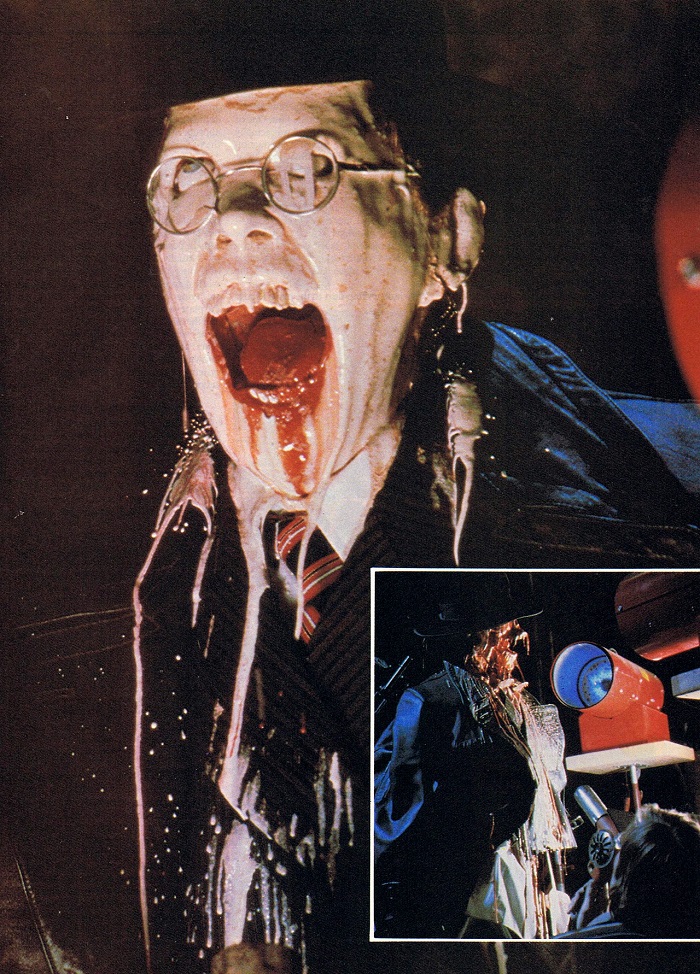

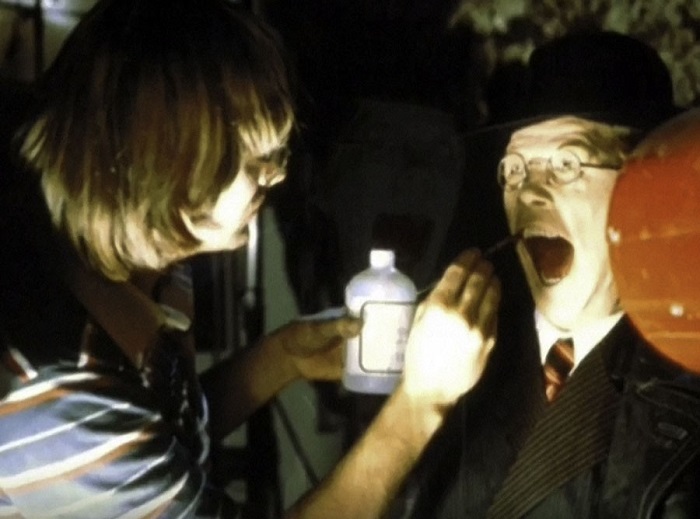

Undoubtedly the most technically impressive part of this scene is the grotesque melting face of Major Arnold Toht (Ronald Lacy). Special effects make-up artist Chris Walas created this gory effect by developing a unique gelatin formula that would melt at a low temperature. He painted thin layers of this in colours of skin tone beiges through to veiny purples and bloody reds inside a mould of Lacy’s head. The melting was then filmed in a time-lapse in front of propane heaters and a heat gun held by Walas so he could control an even melting. Despite the easier-to-melt gelatin compound, it still took the head 10 minutes to melt on camera, so the shot was sped up in post-production.

The Temple of Doom (1984) | Mine Car Chase (1984)

This iconic chase scene, originally written for Raiders of the Lost Ark, sees Indy, Willie (Kate Capshaw) and Short Round (Ke Huy Quan) use mine carts in the tunnels beneath the Pankot Palace to escape the Thuggees.

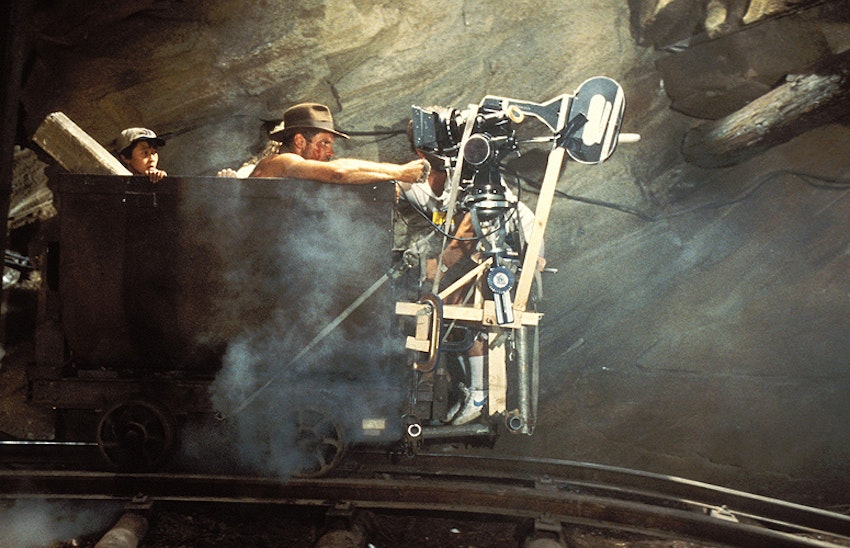

Two sets were required for this scene; a full-scale set for close-ups and a miniature set for the wide and overhead shots. The full-scale mine tunnel track was a short roller-coaster track created by Elliott Scott. Due to its short length, they had to re-purpose it for each close-up shot; by using a variety of lighting, they were able to create the illusion they were in different parts of the mine tunnel in each shot.

The budget for the miniature underground mine track was tight, and the construction costs were based on the size of the camera used. So the smaller 35mm Nikon still camera was chosen, meaning the scope of the set was essentially cut in half, saving them a vast amount of time and money. This Nikon camera was rigged up to truck along with the cars in the mineshaft set, which was predominantly made of shaped and painted aluminium foil, and the tiny carts were pulled along little railroad tracks by thin cables. Puppets were also used to replace the actors, which were animated in stop-motion by Tom St. Amand.

The Last Crusade (1989) | A Leap Of Faith

A number of previously used techniques were utilised again in the third film; a miniature set was made to shoot the explosive plane crash tunnel sequence, which took place in ILM’s parking lot, and a similar gelatine alginate was sculpted on a number of puppets and then blended together with a digital morphing technique to capture the decaying face of the villain Walter Donovan (Julian Glover) before he turned to dust.

However, what really stands out in terms of technical ingenuity in this film is the creation of the invisible bridge. Whilst following a cryptic riddle to pass the temple’s three challenges, Indy finds himself at a ledge overlooking a cavernous chasm where he, as by the instruction of the riddle, has to make a “leap of faith” and step out into the appearing nothingness.

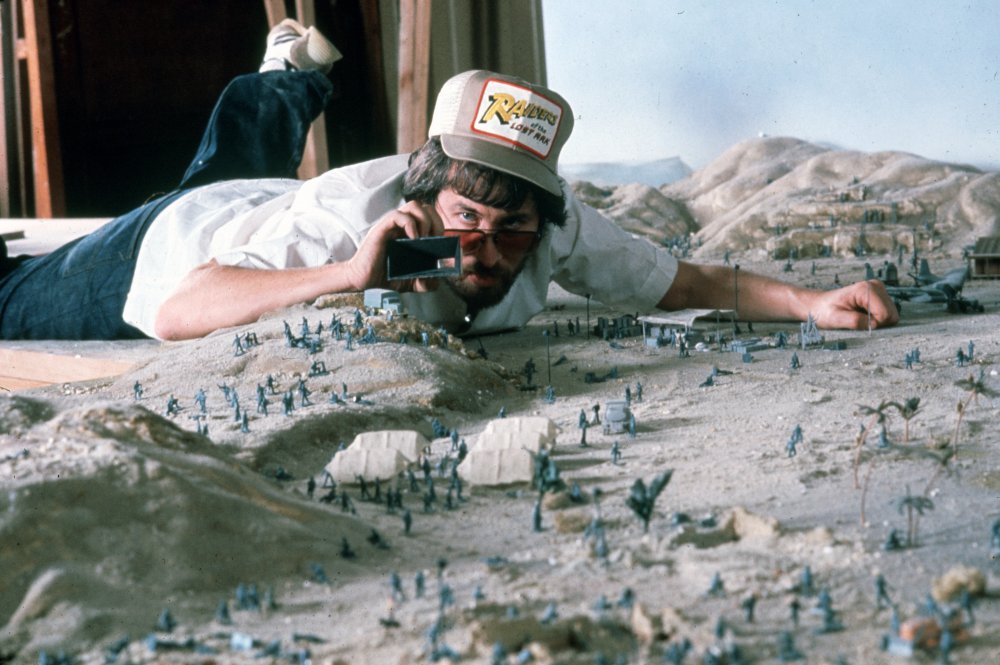

ILM created this illusion with a combination of photoreal matte paintings augmented with miniature physical sets. Yusei Uesugi painted the first shot of the bottomless pit from Indiana’s perspective with a pair of tiny boots placed on a small rock in front of the painting.

The model bridge in the miniature cavernous set was painted by Paul Huston by looking through the camera and sketching the details he saw below so it completely blended in with the rocky background. As the camera moves, the painting no longer matches the background, and the illusion is broken, revealing the structure of the bridge to the audience. Michael McAlister, the visual effects supervisor, noted that this was “the single most challenging concept of the movie” and Speilberg described it as “one of the most interesting things ILM did”.

Hanging Up The Hat?

Clearly, the franchise would not be the same without ILMs creative and progressive effects, which only enriched Indiana Jones’ fun and gritty buccaneering spirit.

It could be because the fallible character of Indy is so relatable that the endearingly imperfect style of the practical and early visual effects compliment him so well. Also, perhaps why the slicker yet somehow borderline cartoon-ish and unrealistic CGI in the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) was less well received.

Still, despite Mangold’s commitment to focusing on practical effects, the trailer has revealed that he won’t be shying away from all modern VFX technologies. A flashback shot of Indy infiltrating a Nazi castle in 1944, taken from the opening sequence, reveals a digitally de-aged Harrison Ford. This new software developed by ILM uses archived footage of a younger Ford to create an uncanny young Indy, which the actor describes as “a little spooky” and “the first time I’ve seen it where I believe it”. The seamlessness of this effect thankfully indicates that the use of new technologies will hopefully be only cleverly utilised to enhance the story and not overshadow it.

As it has been confirmed that this will be Ford’s last stint in the role, many have speculated how the franchise may progress. Could the introduction of Pheobe Waller Brdigers’ character, who plays Indiana Jones’s niece, be the answer and take the lead in a legacy sequel for a new generation? Will the franchise be rebooted from scratch? Or is this truly the last goodbye and a gracious end to a 42-year-old franchise? Only time will tell, and in whatever avenue of new adventures the next era of Indiana Jones may take us, it is in bittersweet anticipation that we currently await to see Harrison Ford’s final caper in the role of the unlikely hero, Indiana Jones.

“Those days have come and gone.”

“Perhaps. Perhaps not.”

Indiana Jones (Harrison Ford) & Sallah (John Rhys-Davies), Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023)