the summer of 1986, Robin Behling was presented with a huge challenge. Formerly an advertising manager at EMI Music, then account director for entertainment-specialist ad agency Cream Creative, Behling had just taken over as creative director of Feref Associates, a Soho, London-based creative agency based which specialised in creating tailor-made advertising campaigns for movies. Despite its impeccable reputation, he’d arrived to find that Feref was struggling financially. It was overstaffed and its directors were, as Behling now recalls, “in hock with the bank”. It had also just lost a massive chunk of its business with the sudden departure of a major client.

Feref’s London Office (Photo courtesy of Feref.com)

But a lifeline was thrown Behling’s way. United International Pictures, a joint venture of Universal and Paramount to distribute their films outside of the United States (along with those of United Artists and MGM), called him with a proposition. “They said, ‘Look, we’ve got a movie we want you to work on. We love what you’ve done, we really want to work with you. And if the film is a success, you can take all of our business.” UIP – which then had around 40 percent of the world market – needed a poster campaign that would truly sell the movie to a British audience, despite its very American theme, and which would draw as big a crowd as possible, despite its male-skewed content. That film was Top Gun. Behling, now chairman of Feref, laughs. “It was a pivotal moment and a pivotal campaign. It was like winning the lottery.”

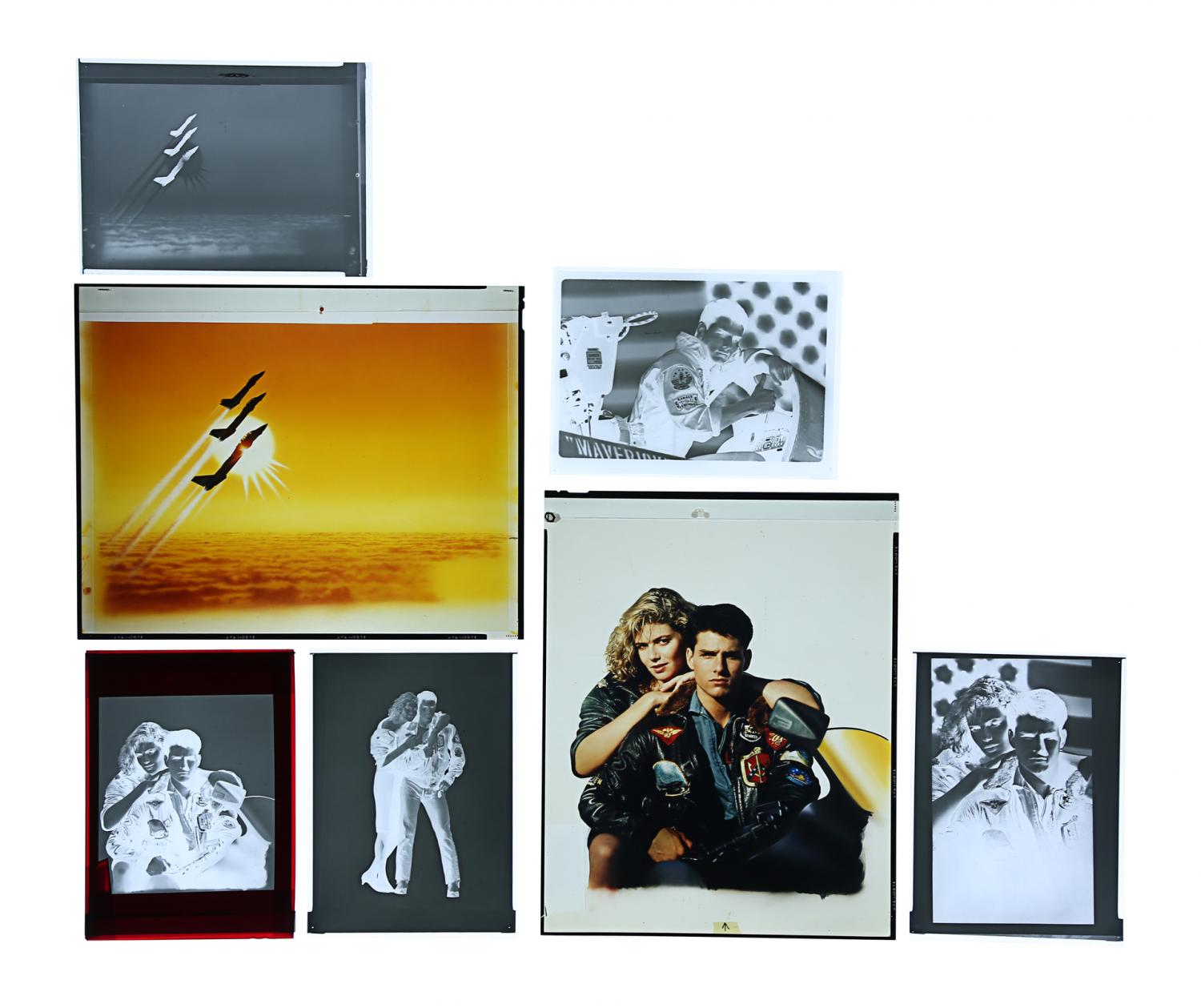

In truth, that win was earned. Behling’s stylish, impactful Top Gun campaign – as shown by the archive transparencies, negatives and print proofs now available for auction – encapsulates everything that makes Feref remarkable in the realm of poster art.

Top Gun (1986), Feref Archive: Original Transparencies and Negatives

“Going back to these times, there was no TV advertising,” Behling explains. “There was no radio advertising. You had a trailer at the cinema, but most of it was print driven. So the poster was critical. You want to make sure you stand out, that people notice it, get excited by it, and obviously go and see the movie. You’ve got to have a campaign that pops, that zings, that has absolute power.”

The power of the movie poster is something that Feref has driven and harnessed throughout its long lifetime: today, as a world-leading marketing agency; in the ’80s, when digital technology transformed the industry and blockbusters became brighter and bolder; all the way back to when Feref was founded, in swinging 1968, by five friends with a big plan.

Fred. Eddie. Ray. Eddie. Frank.

Fred Atkins, a poster artist who was “a star in his own right,” as Behling describes him. Eddie Paul, who took the role of creative director and was Feref’s “driving force.” Ray Clay and Eddie Garlick, ingenious paste-up and layout artists. And Frank Hillary, the retoucher, who would painstakingly scrape photographic prints with a scalpel until they were so wafer-thin you’d wouldn’t notice the edges in the final compositions.

During the ’60s, they’d all worked together at Downton Advertising, which created campaigns for Rank, Gaumont and Odeon. It was, as Eddie Paul once put it, “a bit of a sausage factory. You were just turning stuff out constantly. I can’t remember half the posters I worked on – it was never ending.”

So in May 1968, tired of being overworked and underpaid, this quintet of disaffected, thirty/fortysomething back-room boys set up their own independent shill above Berman’s Hat Shop on Poland Street – though six months later the moved to Little Portland Street, where they remained for most of the ’70s. The company’s name was, quite simply, formed from the first letter of each of their Christian names, perfectly summing up their closeness as friends, united by their creative passion.

“They were all fabulous, clever, talented guys,” remembers Jean Dumpleton, who joined Feref’s photographic department in 1975. “They just wanted to set out on their own, after working for a big organisation where you don’t have the creativity that you perhaps would want.” Dumpleton would stay with the company for 43 years, moving on to become assistant to the head of the studio, then the personal assistant to Behling (“I know where all the bodies are buried,” she jokes).

She describes their original two-floor Little Portland Street base as “the old curiosity shop”: a hive of organised chaos where desks and drawing boards were piled up with papers, and Frank Hillary would liberally dust his compositions with the ash of an ever-present cigar, occasionally blasting them clean with the sharp puff of an empty airbrush. “Frank was very eccentric, an extrovert. It was amazing to watch him,” she remembers fondly.

One time, when an artist came to show them his portfolio, Behling relates, he was instructed to set it aside and handed a ball made of rubber bands. Hillary pointed to three cardboard tubes standing upright at the end of the corridor. “Right, those are the wickets,” he said. “I’m batting. He’s fielding. You’re bowling.” And they played an impromptu game of cricket. “Frank was like that. They would just have fun,” Behling says.

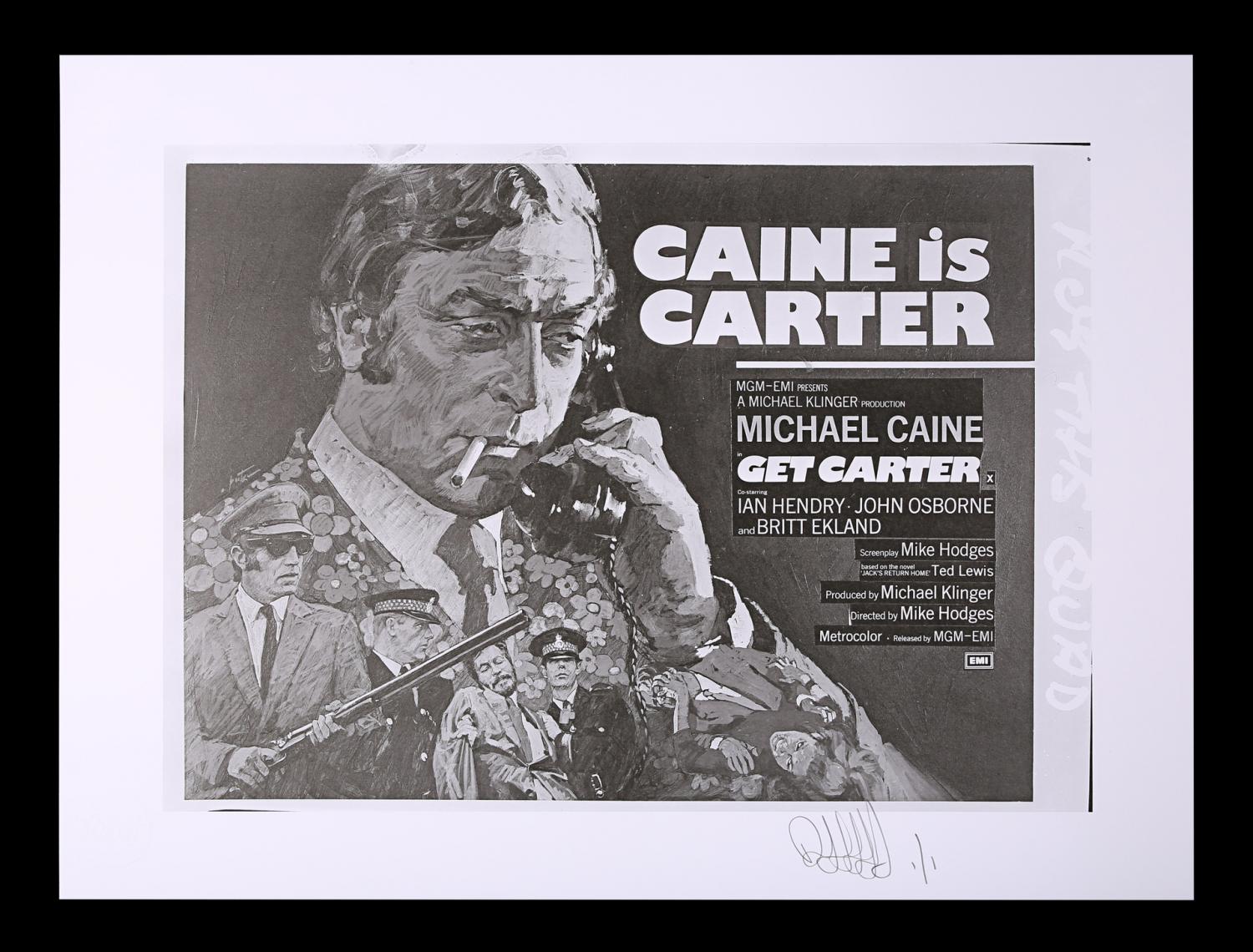

Get Carter (1971), Feref Archive: Original Negatives with 1 of 1 Proof Print

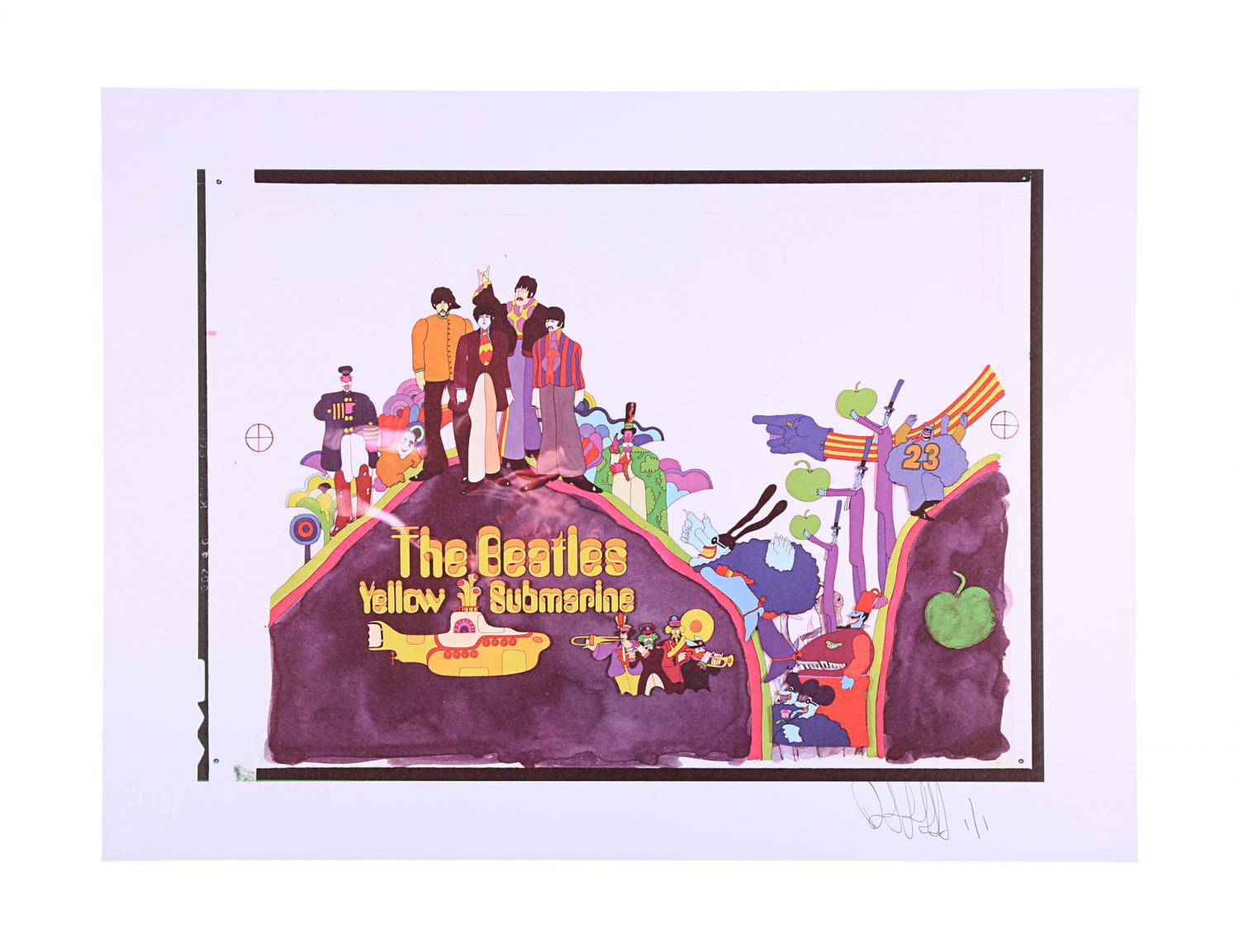

Offering themselves as a cheaper, friendlier alternative to the likes of Downton’s, Feref was soon doing brisk business, and turned out some truly memorable campaigns whose success spoke for itself. This included all three of the original Star Wars movies (“I don’t think we at the time realised how big it was going to be,” says Dumpleton of the first film) and Arnoldo Putsu’s iconic artwork for the 1971 cult thriller Get Carter. Though that particular campaign pre-dates her, Dumpleton remembers the Italian artist as “an amazing guy. He was a temperamental man, but very imaginative. When we were in Little Portland Street, his studio was just next to the photographic department, so I was always in with him, and I used to watch him doing his artwork. He was a very talented artist.”

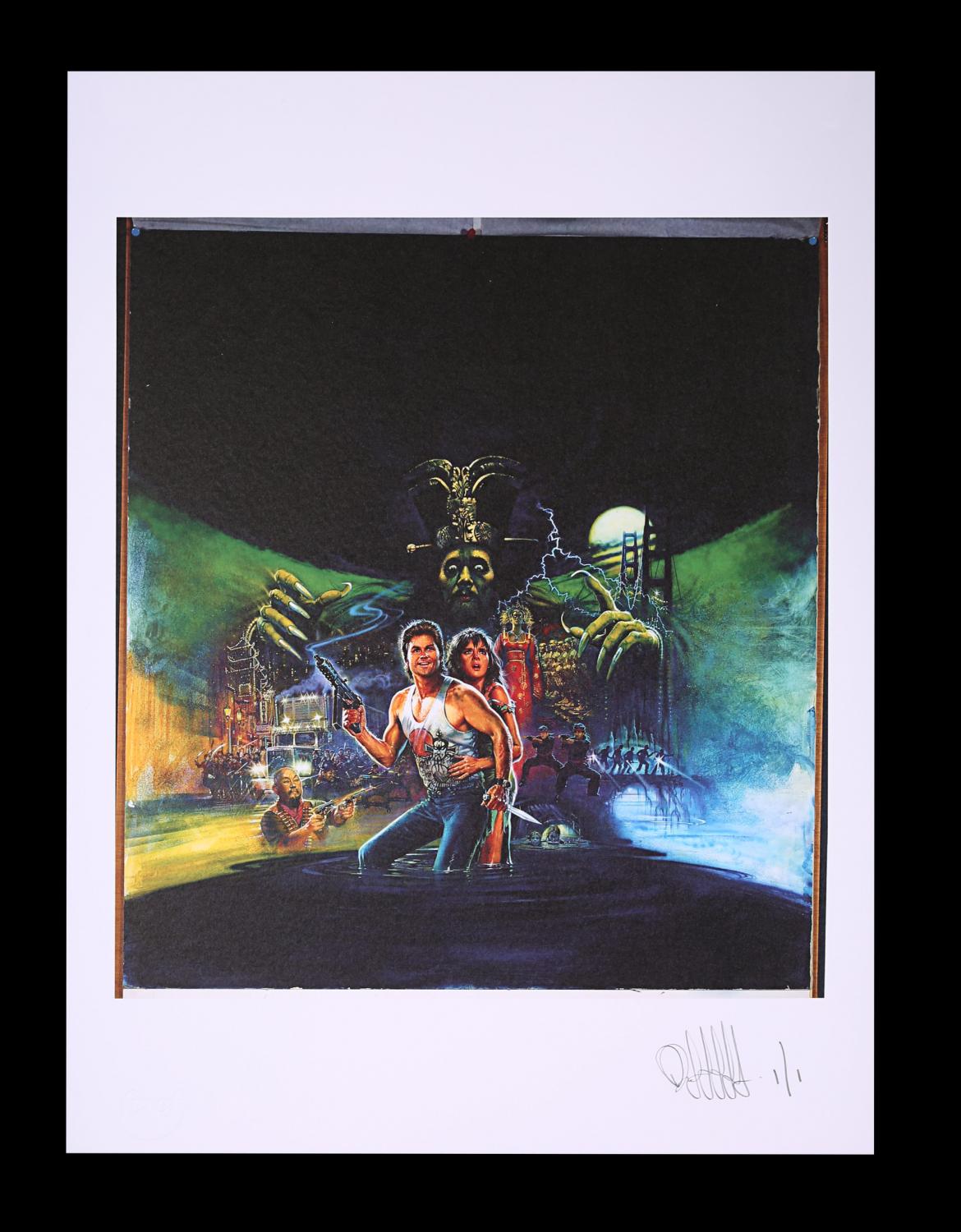

Another regular artist at Feref was Brian Bysouth, who had an office at the company and worked on everything from Bond to Star Trek, while intuitively weathering the transition the company went through during the late 1980s. “He was good fun,” says Dumpleton. “Dedicated. He knew what they wanted, and he would do it. Very rarely did he have to change much.” Behling particularly remembers the amount of time Bysouth would spend painting a single character’s face, working in the detail with a fine brush.

“It was all very hands on,” says Behling of those early days, before Apple Macs and scanners transformed the entire industry – which was soon after he took the creative reins at Feref, alongside chairman Peter Andrews. When that great change was ushered in, with the company founders either retiring or passing away, Feref not only transformed. It also, quite by accident, created a treasure trove.

The photographic department where Jean Dumpleton worked was based in Wells Mews, just north of Oxford Street. There they had a huge Hasselblad static camera to photograph all the original artwork, which was then captured as transparencies. “Then of course, as the computer came along, the photographic department became obsolete,” says Behling. “It wasn’t needed, because everything was captured digitally. So we had all of this stuff in this room – trannies, bits of old black-and-white artwork, old visuals and stuff – and we didn’t know what to do with it.”

Much of it was kept because it was contained in job bags which also included invoices, required to be stored for nine years for accounting purposes. Eventually it was all moved to a storage facility in Shepherd’s Bush, then later, to save storage costs, shipped to a cheap container in Norfolk.

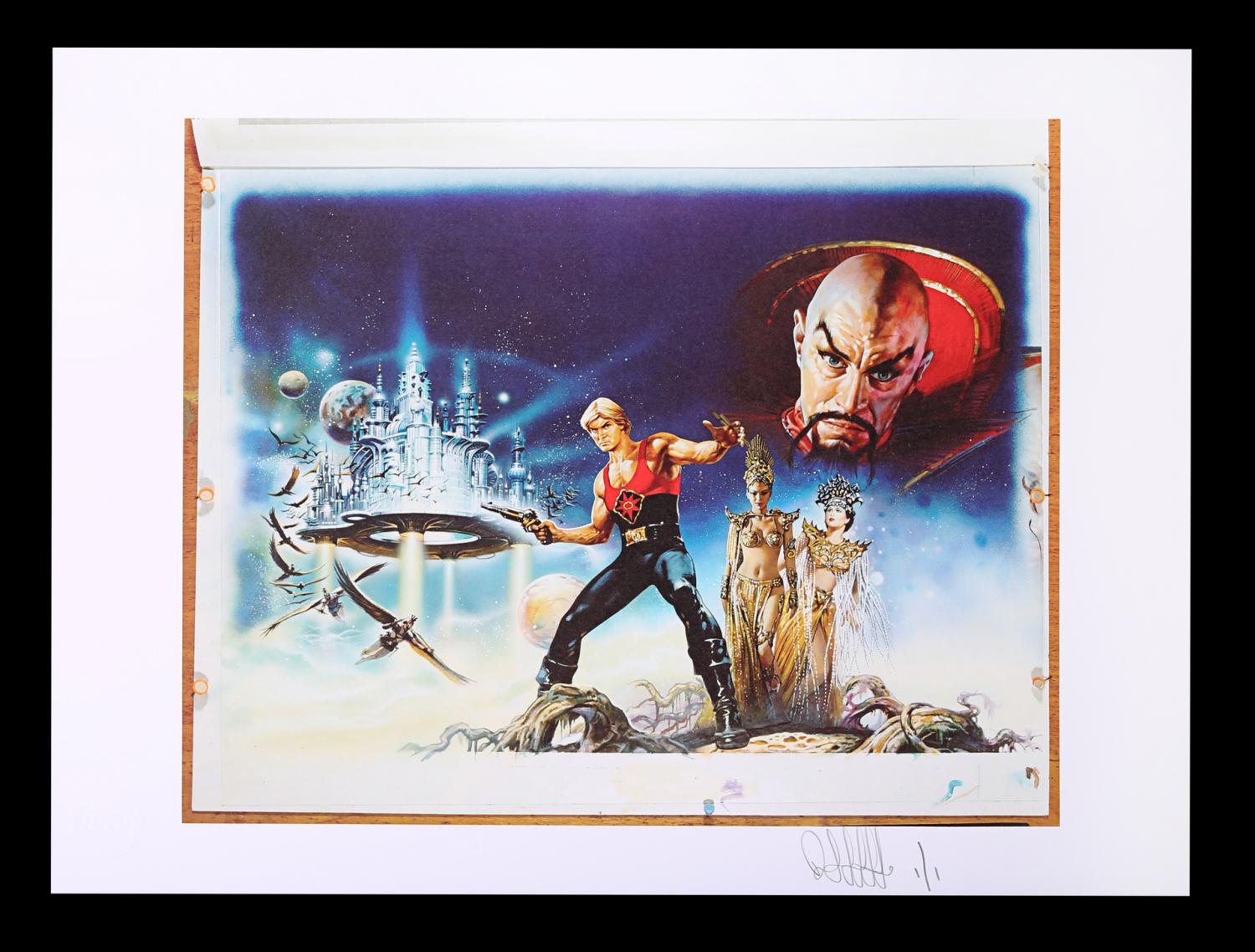

Flash Gordon (1980), Feref Archive: Original Transparency with 1 of 1 Proof Print

“I genuinely thought, ‘why would anyone want all this? Why are we keeping it? Let’s throw it away,’” laughs Behling. “No-one thought, ‘this is an archive’.” But after all these displaced materials were reclaimed, their value as memorabilia became apparent, the transparencies representing first-generation copies of artworks that yield a better quality than digital copies, even.

Speaking at the opening of the Feref Unseen exhibition, held at the Film Distributors Association in Summer 2018, Brian Bysouth admitted that it never occurred even to him that his work would be lasting. “You did your job and then you moved onto the next piece of work,” he said. “It was a continuous conveyer belt of creativity and you were very glad to be producing something that you enjoyed doing. I feel very lucky to have been in the right place at the right time to be the one that was chosen to do the artwork. It’s amazing, and for it to now be collectible for people is a very nice feeling.”

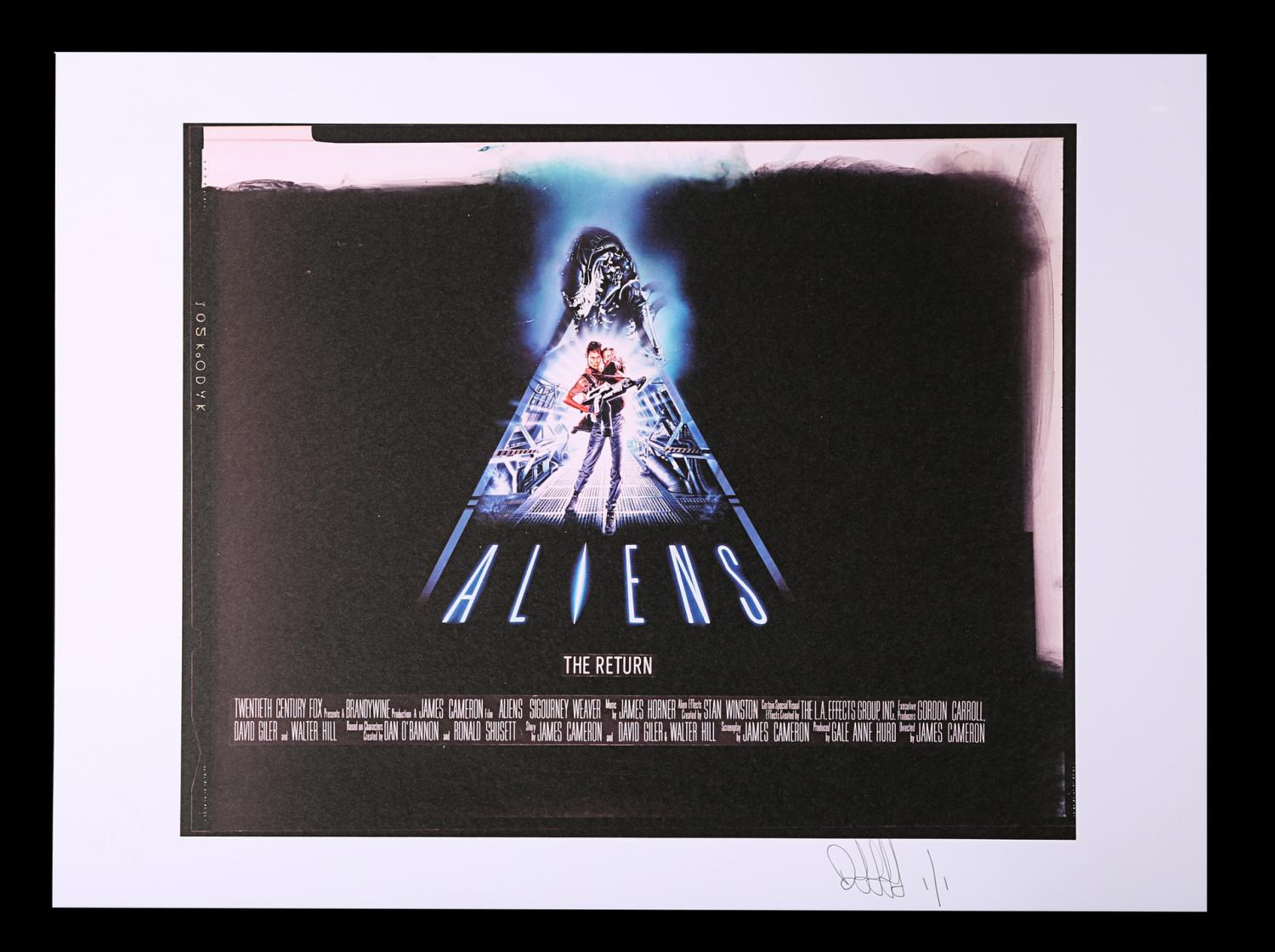

Aliens (1986), Feref Archive: Original Negatives with 1 of 1 Proof Print

The collection – 200 items of which are going under the hammer as part of Propstore’s upcoming Cinema Poster Live Auction – is testament to Feref’s appeal and value to their movie-studio clients, for whom a poster campaign was, and still is, seen as crucial to securing a strong opening weekend at the box office. But there is more to the company’s continuing success, Behling insists, than just the art itself.

“Our role was what I used to call ‘accelerated selling,’” he says. “We had to take a campaign with no credibility, with no pedigree, a brand new film, and we had two-to-three weeks to launch this movie, to get the audience to go: I’ve got to go and see that. People trusted us.”

Behling tells one story, about a meeting he took with – as he describes them – the producer of “one of the UK’s biggest franchise movies about a spy in a tuxedo.” When he walked into the office, she was on the phone to a director who was begging for more time to finish the film, though they were only weeks away from release. “And she said, ‘I need to go now. I’ll phone you back, because Robin’s here’.”

Star Wars: Return Of The Jedi (1983) – FEREF ARCHIVE: Original Negative with 1 of 1 Proof Print

Another time, while working on the campaign for the George Lucas-produced fantasy adventure Willow (released in 1988), Behling travelled to Elstree Studios to present his visuals to Lucas in person. “I was ready to deliver my pitch and he just went, ‘That one. That’s the one,’” Behling recalls. When Lucas asked to have the campaign ready by the end of that same week, Behling pushed back. “It’s going to take three to four weeks,” he insisted. “Oh,” said Lucas, “Okay. Fine.”

Behling’s point is that he, and Feref as a whole, offered a level of confidence and assurance that their clients, even the most powerful people in Hollywood, appreciated. Plus, he points out, “a campaign is a piece of art that is a legacy that encompasses all their hard work. They can stick it on their wall as a producer and go, ‘I worked on that. It sums up everything we did.’”

For Jean Dumpleton, who retired in 2018 and now lives in Cheshire, Feref has a different kind of legacy. One that is more personal, and reflective of the creative environment fostered at the company since its inception in 1968. “It was such a fun place to be,” she says. “It wasn’t the best paid job in the world, so you stayed for love, really. We did things together. We were friends as well as work colleagues. It felt like a family.”

Find the full Propstore Feref Archive collection up for auction now in our 22nd April 2021 Cinema Poster Live Auction at propstore.com/posterauction.

Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter and Facebook. And remember, you can explore so much more at our archive and see the extensive range of film and TV items we have for sale and auction over at propstore.com!